Generous Gift to School of Art from Harold Altman A'47

POSTED ON: February 21, 2024

Although the artist Harold Altman (1924–2003) prized painting and drawing, he was especially drawn to printmaking for what he deemed its egalitarian quality: "I think in a sense, the original print is a very democratic kind of distribution of art. And when you do a unique work, only one individual has that work or one museum. However, a beautiful print can be in several hundred different locations in so many different countries."

That same spirit imbues his 2023 gift to The Cooper Union, $1.2 million to the School of Art.

"He felt so strongly about Cooper that he could not talk about that without tearing up," his daughter Jessie Beers-Altman said. Not from a wealthy family, Altman believed that, though he’d been born with talent, it was The Cooper Union that gave him the opportunity to use it. "He was discerning with his philanthropy," said Beers-Altman. "This one mattered a lot to him."

Altman had created a giving instrument called a Charitable Remainder Unitrust (CRUT) that distributes a fixed percentage of the trust. He determined that for its first 20 years, the CRUT’s dividend would be given to his five children and after that time, donated to The Cooper Union. The gift is unrestricted, so that as art students’ needs change, the school can apply funds accordingly.

Adriana Farmiga, acting dean of the School of Art said, “These unrestricted funds give us significant flexibility in addressing our students' needs, and we're incredibly grateful for this gift from Harold Altman.”

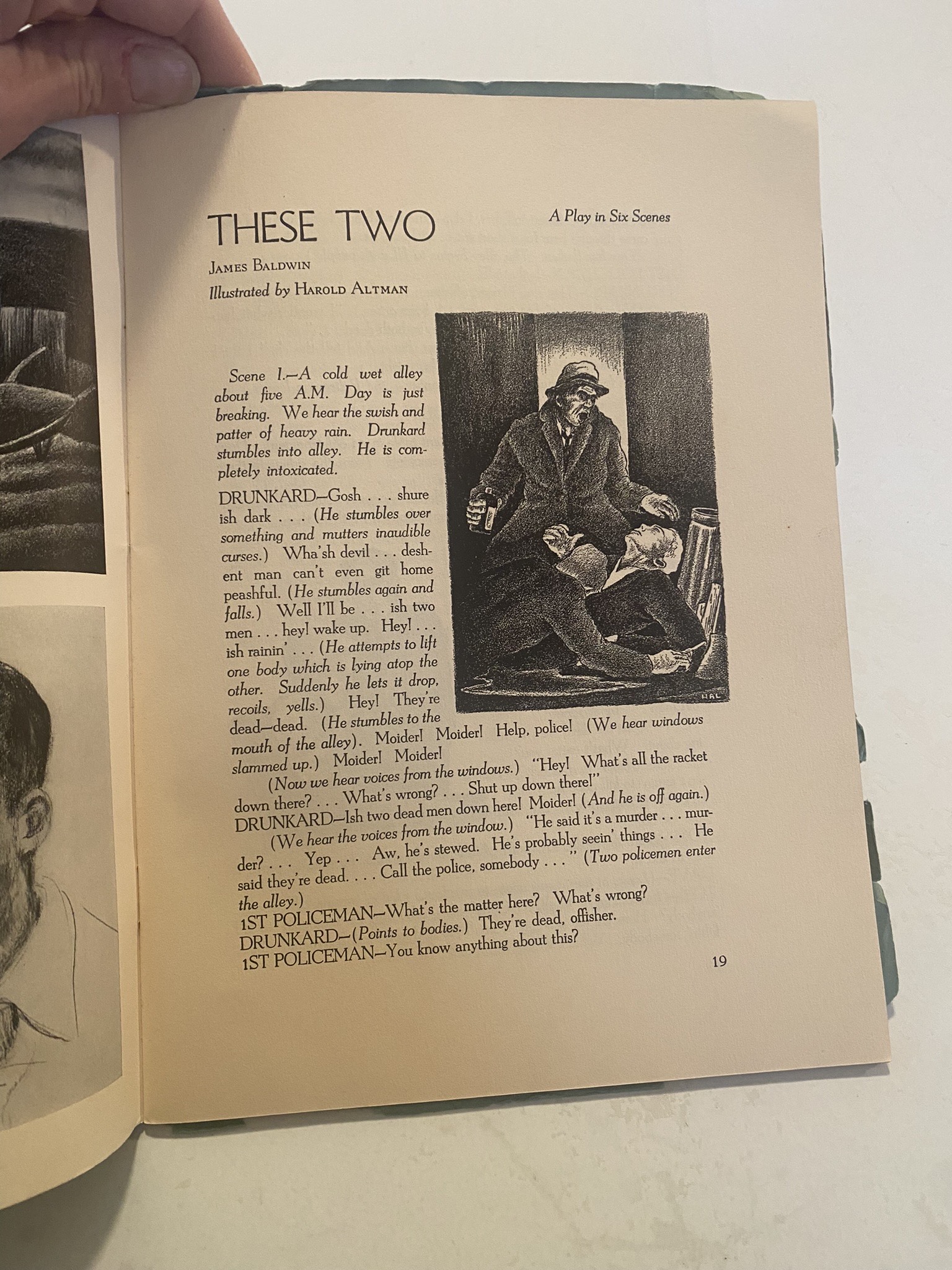

Altman had been an artist since childhood. His inclination to draw kept him from concentrating in school but when he began taking free art classes for children offered by New York University (NYU), his gifts were readily apparent. At DeWitt Clinton High School, he worked as the school newspaper’s chief illustrator, making drawings to accompany stories by his classmates, James Baldwin.

Although he began Cooper in 1941, earning mediocre grades, his education was interrupted by a three-year stint in the army as part of a camouflage unit in Europe. When he got back to New York, he noted in his journal, "You need to get serious." After the war, he earned high grades, which clearly reflected a newfound direction.

His commitment got results: over the course of his career, Altman received two Guggenheim Fellowships, a Tamarind Lithography Fellowship, a National Institute of Arts and Letters Award, a Fulbright-Hayes Senior Research Fellowship for work in France, and a National Endowment for the Arts Grant. He received a Cooper Union Presidential Citation Award in 1975 and was inducted into the Cooper Union Hall of Fame in 2009. Most of his teaching career was spent at Penn State University where he was professor of art since 1961.

Beers-Altman wrote that in his youth, “my father became fixated on themes of privilege and oppression. Many of his pieces during this time highlighted those themes. He frequently depicted coal miners, as well as street market vendors. His early focus on these themes influenced his lifelong commitment to progressive/Democratic values. During his time at Cooper and in the years following, he considered becoming a political cartoonist.”

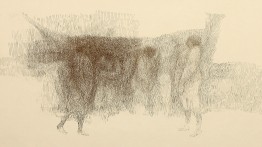

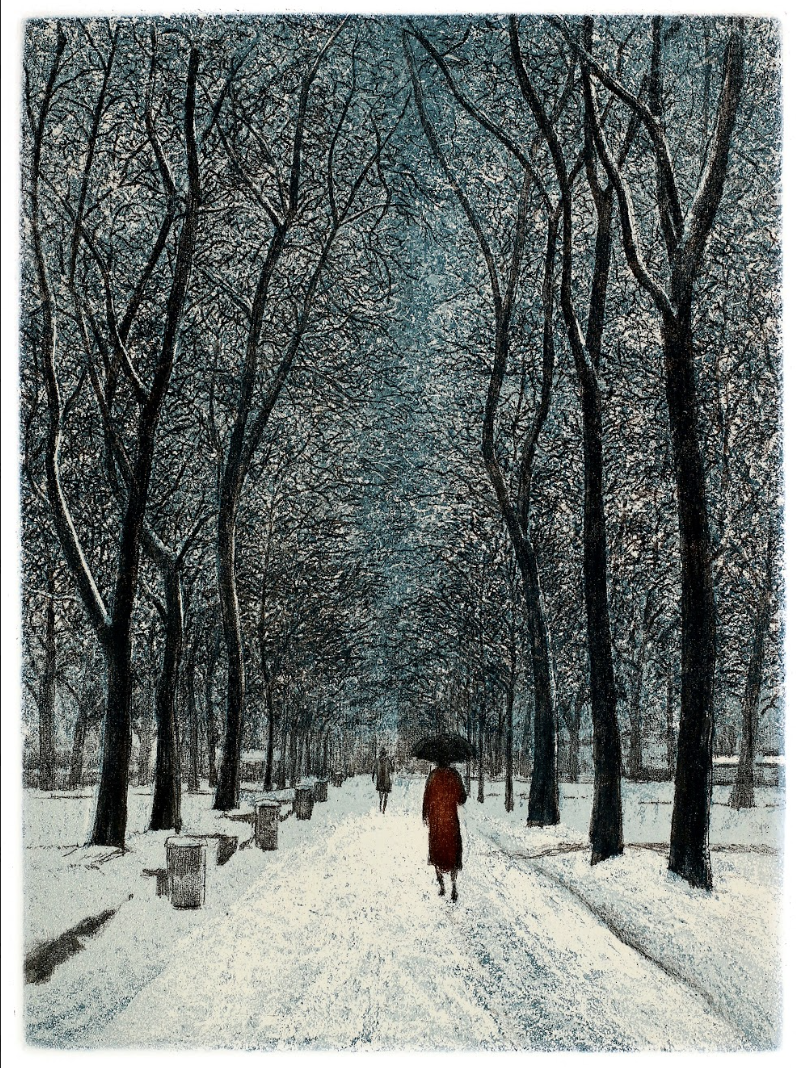

The work that first brought him to prominence were black-and-white etchings that melded human and landscape subjects into one abstracted whole. When he was one of only two American draftsmen chosen for the First Paris Biennial, the art critic Dore Ashton praised his mastery of the art despite being only 35 years old at the time. Noting how his work had quickly matured, she wrote in The New York Times that his vision was “no longer distracted by incidental detail” and that he had the confidence to include what she called "spatial pauses" that focused his prints. Cat, an etching from 1960, epitomizes Altman’s economy and precision with mark making: it shows a street scene with a cat standing in the lower third of the picture plane, clearly identifiable yet made of just a few short lines.

Throughout his career, Altman remained fascinated with human smallness in the context of the larger world, but he expressed the theme in markedly different ways as he grew older. For one, he introduced far more color into his prints. These lithographs often show tall trees covered in various colored leaves. The painstaking process required of lithographs caused him to joke that he kept a leaf-making machine in his studio. But the work managed to let Altman bring his art to many audiences, just as he wanted. He sold prints to individual collectors as well as hospitals, companies, museums, including more than 40 at the Museum of Modern Art and more than 40 at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and the Brooklyn Museum. His work can be found in prominent institutions worldwide, including the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam, the Kunst Museum of Basel, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Copenhagen, and the Bibliotheque Nationale of Paris.

He also has a piece at the storied Victoria and Albert Museum in London. When his daughter Jessie visited him in the UK as a teenager, he took her to the V and A, as it’s commonly called. In the middle of their visit, he mentioned he had a small piece in their collection. Beers-Altman insisted they see it and she requested a curator to take the piece from storage so she could have a look. She recalls her father being slightly embarrassed by the fuss, but pleased by her interest, nonetheless.

Today, Beers-Altman is surveying her father’s oeuvre in a documentary film she’s been making called Inherited. Her father left behind a huge body of work as well as troves of materials, receipts, letters. Going through all of it is a big job for Beers-Altman, who moved back to the State College area in 2020. (Altman is also survived by his son, Eli Beers-Altman. His three older children from a first marriage, Toby, Evan, and Ann, have all passed away.) Parallel to its exploration of his art, the film asks questions about how we all handle the death of loved ones, how they live on in objects, and what we choose to keep and to give away. Along the way, she’s learned about aspects of her father she’d never known. But one consistent thread: he cared deeply that opportunities be made available for all regardless of income. Harold Altman’s gift to Cooper makes that commitment a reality for generations of students to come.